Heart of Conservation Ep #37 Show Notes (Edited)

Summary

Nandini sheds light on the innovative use of technology in conservation efforts. We discuss the diverse range of technologies employed in conservation, with a focus on spatial technology involving satellite data, drones, and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). Our conversation delves into various collaborative projects across different landscapes, highlighting the foundation’s expertise in cartography and the use of technology for land restoration and riverine wildlife conservation.

This episode also showcases the foundation’s pioneering work in utilizing drones for the study of river dolphins and gharials, emphasizing the ethical and collaborative approach taken in wildlife research. The episode captures the legacy of Technology for Wildlife Foundation, emphasizing its commitment to using technology ethically and thoughtfully to benefit wildlife, habitats, and local communities.

Our legacy should be remembered for prioritizing impactful grassroots action through technology for conservation.-Nandini Mehrotra (Technology for Wildlife Foundation)

Transcript

0:00:09

Host: Lalitha Krishnan: Hi, I’m Lalitha Krishnan, and you’re listening to heart of conservation. I bring you stories from the wild that keep us all connected with our natural world. Today I’m speaking to Nandini Mehrotra from Technology for Wildlife foundation, a NGO based out of Goa. I have been chasing technology for Wildlife foundation for a couple of months now. Somehow the opportunity kept slipping through my fingers till now and just in the nick of time. And you will find out why soon.

0:00:37

Lalitha Krishnan: For now, I’m very excited to be speaking to Nandini, who’s the Program Manager, Technology for Wildlife foundation. She has an MPA in Environmental Policy from Cornell University and oversees the applied research projects. Her interests lie in the intersection of conservation technology and government. Welcome to heart of conservation, Nandani.

0:00:59

Nandini Mehrotra: Thank you so much.

0:01:00

Lalitha Krishnan: So, you know, Nandini, technology for wildlife sounds like such an innovative space to be in. You know, I know they’re very amazing ways of employing technology, so I’m very excited to hear your stories. Perhaps could you start with, you know, introduce us to some kind of technology employed in conservation efforts first, and then tell us all about technology for Wildlife Foundation’s expertise in this specific field?

0:01:28

Nandini Mehrotra: Sure, I think. I mean, I’d like to start by just mentioning that conservation technology itself is not new. It’s just changed form, like all the technology in our day to day lives. And it is, of course, like an increasingly growing field as smart technologies also continue to improve. So, yeah, technology for wildlife work very much comes from a place of seeing that if this technology is available and growing and agile, how can we use it for the betterment of the planet?

0:01:58

Nandini Mehrotra: But the kind of technologies are so varied. They include radio tags to camera traps, acoustic devices, sonar. Like every technology that exists in our day to day lives, conservationists have tried to adapt to see what we can do to use it for conservation. For us at Tech, for Wildlife, though, we mostly specialize in spatial technology, so we don’t work with this whole range of technology. We work a lot with satellite data and spatial data, so that can be things that are taken from satellites or also even just gps on your phone.

0:02:32

Nandini Mehrotra: We also use drones, both for their visual information, but also because they record spatial data as well and we use something called ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles), which are kind of like tethered underwater drones. They basically are like underwater cameras, which have motors and we can direct them.

0:02:52

Lalitha Krishnan: So that’s cool.

0:02:54

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, it’s quite fun to use them, but, yeah, that’s kind of the range of tech that we use.

0:03:01

Lalitha Krishnan: So, what other wildlife organizations do you collaborate with and in what range of landscapes?

0:03:08

Nandini Mehrotra: Most of our projects are all collaborative. We are always looking for partners who are doing impactful work and we feel they are aligned with. And if there’s a case where the tech that we have can assist with their work, then that’s how we choose our projects. So, the organization and work are really spread across the country and varied in that sense.

0:03:32

Lalitha Krishnan: Yeah.

0:03:33

Nandini Mehrotra: Goa, where we’re based, we collaborate quite a bit with the Goa Foundation and with WCT Wildlife Conservation Trust, we’ve been collaborating for the last couple of years in Bihar around freshwater ecosystems and wildlife. With Dakshin and WWF, we did some work in Orissa, around Olive Riddley turtles. In Ladakh, we work with IISER Tirupati. We also have an exhibit going on with the science gallery in Bangalore, where we compile our work on mangroves, along with three visual artists that we collaborated with.

0:04:13

Nandini Mehrotra: So that’s an exhibit that’s been running for the last few months, and this is the last month that it’s running. I think ecosystems and projects are quite varied.

0:04:22

Lalitha Krishnan: So, you know, can you speak about how you use cartography for conservation with specific partners, perhaps?

0:04:31

Nandini Mehrotra: Sure. So, one of the main reasons that we specialize in spatial technology is that we believe that a lot of time conservation, especially conservation, especially terrestrial, but really, everywhere is a land use position, and maps influence these positions. A lot of time, the visualization is easier for people to conceptualize, see our way of being able to use our skills to do work. So, we do use maps quite a bit.

0:05:02

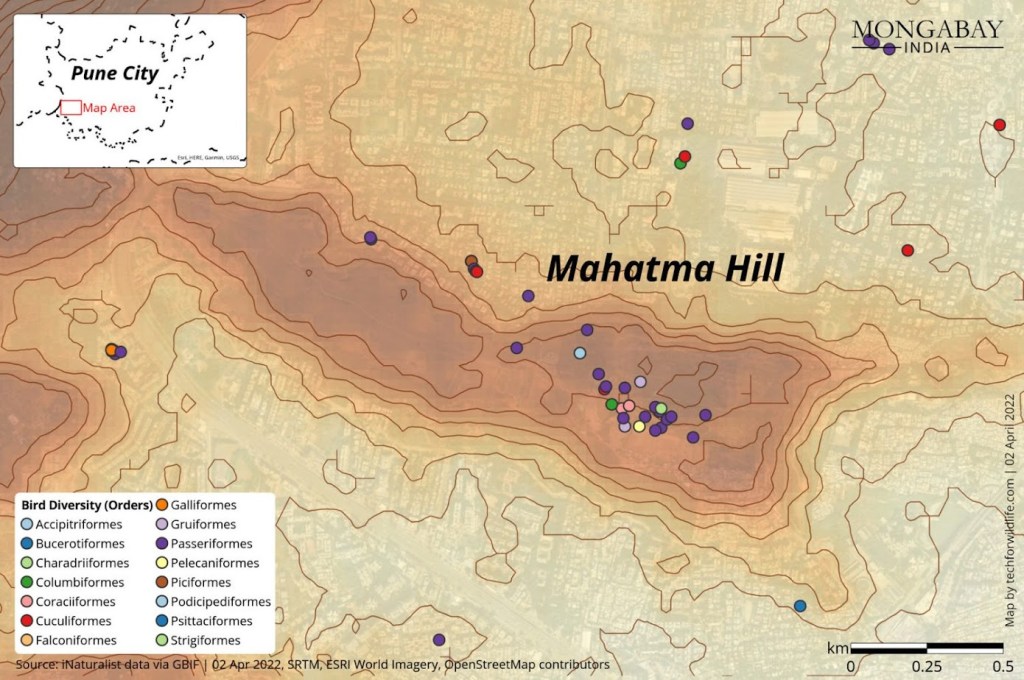

Nandini Mehrotra: Some of the ways that we’ve been doing this is through collaborating with different partners, one of them being Mongabay India. We worked with them for two years. We did over 40 stories with them. So that covered a range of whatever topics they were working on, anywhere that, like visual mapping, could aid the story in any way. So we worked on those, on static maps, moving gifs, dynamic maps.. different and many things.

0:05:30

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, many things. Over 40 stories where must have been at least double of those maps. The other one that we’re quite proud of is there’s an update coming of Fish Curry and Rice, which is a book written by Goa Foundation and is currently in the being updated. So that entire book is about Goan ecology and environment. It’s kind of like a current state of affairs report, and we provided the cartography for that as well. For 20 maps.

0:05:59

Nandini Mehrotra: So that book should be published this year as well. So, we’re looking forward to seeing that.

0:06:04

Lalitha Krishnan: Quite a range. I shall look forward to Curry and Rice myself. What a catchy title.

0:06:12

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, yeah. There’s, I think, two versions of the book already out. Fish curry and Rice. Also in Goa.. I’m not sure if you’re familiar with the Aamche Mollem campaign, but it’s a citizen’s movement that’s been running now since 2020. It was questioning three linear infrastructure projects that are passing through the state of Goa. So it’s a collaboration of activists, researchers, lawyers, kind of looking into the impact of these projects and trying to see what is the way forward that can be most beneficial to everyone and, like, least negative impact on the environment.

0:06:55

Nandini Mehrotra: And we also did cartography to be able to support that, both for analysis and for communication.

0:07:05

Lalitha Krishnan: Nice. So you seem to have had a busy 2023, and of course, you’ve done a lot of work based out of Goa. One of the areas you cover is technology for the restoration of land. Could you tell us more?

0:07:21

Nandini Mehrotra: I just wanted to start by talking about restoration in general as a growing field. It’s. Yeah. To both conserve biodiversity, restore land use, address climate change. It’s got many benefits and we’ve been seeing an increasing interest in this as a way to address some of these challenges. So, our aim was probably to see how can we use the tech and skills that we have to be able to enable and assist some of these processes.

0:07:55

Nandini Mehrotra: A lot of the people working in restoration need to be able to quantify and monitor their land better and to be able to see how to plan their activities more. So that’s kind of where we were coming in. So we were very lucky. We have two amazing colleagues, Alex and Christina, who are working to restore 150 degraded forests in Goa western parts. And along with many collaborators, we’ve been trying to see what we can do for this. So, there’s actually already a lot of research and tech that’s being used to assist restoration. But what we found is that some of the technology that normally people have written about includes technology that’s inaccessible to a lot of, at least NGO’s in the country.

0:08:44

Nandini Mehrotra: Like us, it was inaccessible. So, we realized that it must be similar for other NGOs in the country as well as in the global south generally. So things like LiDAR and multi spectral drones are still not so accessible, both in terms of cost and regulations… A bunch of things. We wanted to see from the tech and resources we already have, from as open access and affordable as things can be, what can we create?

0:09:09

Nandini Mehrotra: So, we’ve been using a combination of ground data, and basic off the shelf RGB, which is just visual color drones and satellite data to understand the land a bit more. So doing spatial analysis with the satellite data to understand levels of degradation, different factors of degradation, and then using our drones to see what more visual information can we get within computer vision models to extract some of this data and make the satellite models better.

0:09:44

Nandini Mehrotra: So, while we are giving all of this input to Alex and Christina, that piece of land. So hopefully it will be helpful for them to be able to see, okay, what does the entirety of the land look like? And to be able to see year by year how it’s changing. But we currently condensing the whole workflow and we’ll be trying to put it out soon so that it’s also useful for anybody else working on similar projects, because as I was mentioning, there are quite a few.

0:10:11

Nandini Mehrotra: So that’s what we’re working on in terms of restoration.

0:10:16

Lalitha Krishnan: Oh, cool.

0:10:17

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, I mean, it’s a really beautiful site, and it’s in the ghats, it’s very close to protected areas. So, in that sense, it’s also just an amazing place, even in terms of biodiversity. If that land is restored, it is like, it does have a lot of trees. It’s just the quality of the forest has degraded. Yeah, it is a beautiful piece of land.

0:10:41

Lalitha Krishnan: Yeah, sounds like it. Okay, so what is the other, project Technology for Wildlife is working on? I read about the riverine wildlife. Do you want to talk about that?

0:10:53

Nandini Mehrotra: I would love to talk about that. It’s definitely one of my favorite projects that we worked on. Just generally, for the context, we have obviously, incredible rivers and freshwater ecology in this country, and river dolphins and gharials are two of these. River dolphins are endangered. gharials are critically endangered. And we wanted to see what we can do to better understand and, how we can use our skills to protect these species. So, the experiment was kind of in multiple parts, in one.

0:11:28

Nandini Mehrotra: This is all in collaboration with Wildlife Conservation Trust. In one stint, we tried to combine many methods to see what is working for which species to understand them better. So, we, of course, were using drones for this, but they were also using acoustic devices, also just boat based visual methods to be able to understand one: How are species reacting to all of these? What can we do with minimal disturbance and what aspect of their behavior are we getting the best? So that for future surveys or any way to plan conservation efforts, what means should we be using? So, first, two of our trips were really around being able to understand this better.

0:12:13

Nandini Mehrotra: And recently we then built on this. So, for gharials, we realized that using drones was a very useful way to be able to cover large distances and disturb them minimally, get a better assessment of their numbers, size, bunch of things, as long as it’s done with a lot of care. They’re very sensitive to sound, so they have to be flown at a decent height above them. With river dolphins, we found that maybe not so much for counting them, but river dolphins are…

0:12:50

Nandini Mehrotra: They stay underwater and only come out to breathe for a fraction of second. And, they live in the Indo-Gangetic basin, and the water is extremely murky. Using underwater cameras, not really an option there. So, to be able to understand more about the species, their behavior, it is very hard to document. So, most of the accounts are quite muted because they’re seen visually. So, we found that in this case, using drones, we were able to capture a lot of video and video footage.

0:13:25

Nandini Mehrotra: So then we went back for our third round of fieldwork this year. We went to hotspots where we knew there was a lot of dolphin activity, and we were just staying there and observing these dolphins. So now we are building a lot more information on their body size -their size and their body condition based on that, and being able to build a profile of dolphins in a certain area in the Ganges. What is the condition, what are their sizes to understand, like, the profile of the population.

0:13:57

Nandini Mehrotra: A lot of this has kind of been experimental and innovative. It’s been a lot of fun to learn about, and Wildlife Conservation Trust is a incredible team, so it’s been a pleasure.

0:14:09

Lalitha Krishnan: Oh, nice. So, are you the pioneers in doing this? I’m not sure I’ve heard of dolphin studies with drones.

0:14:18

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah. So, drones have been used to study dolphins around the world, but this has mostly been done for marine dolphins. I think also the Amazonian River dolphin people have used drones in. Yeah. So while some of it is still experimental, like, I don’t know of anybody else yet who has done size estimation of river dolphins in Goa. At least nothing has been published.

0:14:49

Lalitha Krishnan: Right. So, you know, you did not say that it was hard, but what are the challenges you face in your line of work? You know, like, do you ever have to deal with community and I am sure weather. And stuff like that?

0:15:03

Nandini Mehrotra: It ranges, really. There’s, of course, challenges that you have to address within the technicalities of the work. And then there’s more broadly the field. It’s interesting you brought community up so far. Actually, we never faced an issue with the community, with any community. I mean, yeah. For one, that we always work in collaboration with organizations that have been working in an area for a while and have a rapport with people there.

0:15:33

Nandini Mehrotra: You would never want to go into a place and, you know, not do anything that might not respect or scare anybody. You never want to be able to hide what you’re doing. So, anybody who has questions, any curiosity, you want to welcome that. I think ethics is always like a very tricky thing in this field, especially around drones, because there’s many cool things that you can do. But also, there are definitely concerns around privacy and safety that there’s always scope of things being misused, if not done sensitively.

0:16:12

Nandini Mehrotra: And also, I think drones also have a perception that make people also hesitant. Understandably so. So, I think one of the things for us has been also, you know, how to navigate this in a way. We have been very keen to distinguish ourselves, to make sure that we, you know, want to make it known that we will not do anything that would ever risk or harm anyone, even if it comes at the cost of not being able to collect the data we want to.

0:16:40

Nandini Mehrotra: We would rather give up that day of fieldwork than do anything that would make somebody uncomfortable. But that being said, the processes of how to go around it are so are not that clear. Right? It’s not like there’s a regulation or like a set protocol around how should you go around the ethics of when you’re doing a wildlife project or any work for that matter, and then you, tend to do whatever is in your capacity and possible. So because this was important to us, we kind of had our own internal checklist of what we were or were not okay doing.

0:17:16

Nandini Mehrotra: But that also comes within its own limitations of what we have read, what we are exposed to, and also what is possible. Right? We are also a small ngo going for a few days of field work somewhere. This is something that would require, say, like written informed consent of an entire community. Like, that’s not something that was within our reach, even. That requires like, a lot more systems that would…

0:17:45

Lalitha Krishnan: Yeah, but that is so good to hear. I mean, you must have done something right if you haven’t had any trouble so far. You know, you are sensitive and doing the right thing.

0:17:57

Nandini Mehrotra: I mean, honestly, people are intelligent and even if they do not know exactly what the tech is… If you are not trying to be sneaky about it, it’s quite straightforward. And of course, if somebody is not comfortable, then you just do not do it. And then if there’s in a place, if there’s ever a question of not being able to ask somebody or not being able to issue get the permission, or you just don’t do it.

0:18:23

Nandini Mehrotra: For us, that has always been the approach.

0:18:26

Lalitha Krishnan: 2023 was also eventful because the great loss of your founder, director Shashank Srinivasan, from what I read, he seems to have been a really passionate and charismatic leader. Would you like to speak a little about him and his work in Ladakh, perhaps, or just anything you would like?

0:18:48

Nandini Mehrotra: Definitely. The very existence of the organization is, of course, completely owed to Shashank, and he was an incredible person and conservationist and leader. I think he was really a very insightful creator in that sense. To be able to see a gap in the conservation ecosystem and create an organization to fill that gap, I think that’s quite…That’s not a small feat at all. I think that’s definitely something that deserves recognition. I think that’s something incredible to have achieved in his lifetime. And even within the organization, I think his creator instinct, like, to be able to, the way the projects are developed and conceptualized, always makes place for impactful work and prioritize that in what we’re doing. And, just, you know, what kind of work environment do we have? Like, what kind of work environment do you want to work in? What will help you flourish and then trying our best to create that. And I think that’s really, it takes many different skills and abilities for somebody to be able to create that, so that we’re very lucky to have had a workplace like that. And of course, he was incredibly skilled as a spatial analyst and card operator. So, in that sense, also an incredible creator.

0:20:14

Nandini Mehrotra: And, yeah, his projects, he was involved in every project, of course, that we were doing. But Ladakh, I guess, was like his longest running association professionally, I think his interest, I think, began during his own Masters thesis while he was there. He loved the black neck crane there. And during his masters, he was working with the community mapping with the Changpa community there.

0:20:40

Nandini Mehrotra: So, it began with that. And then he went back multiple times with different organizations. I think he went back to WWF as well. And then in 2019, he got a National Geographic explorer fund. So that was also for work in Ladakh. So, there we documented nine remote lakes, both aerially using drones and underwater using our ROVs. Yeah, it was incredible. Part of it was just that explorer bit, which was just there…

0:21:14

Nandini Mehrotra: They were quite remote lakes. Some of them were not even open for on the tourist circuit. So, to be able to document and share that also with everyone, because there’s always a sense of, like, how can anybody want to protect something that they don’t know or haven’t seen? And also, again, the aerial and underwater footage, again, as far as we know, it was one of the first things that a lot of it was being captured for these breaks, especially underwater, because it’s too dangerous for humans to dive in.

0:21:45

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, a lot of that was incredible to explore. And there was also a component of it which was looking at plastic. Plastic waste, because all these lakes are endorheic, meaning they don’t have like a river outpost. If any contamination ends up in the lake, that means it’ll stay there until somebody takes it out. So, it was also about looking at, is there plastic contamination even in the remotest of remote lakes in India? And if so, how much? And what are the companies, what kind of litter is there? So, we spend a lot of time collecting garbage around.

0:22:22

Lalitha Krishnan: God bless you guys. I always say that to anyone who collects garbage. But, wow, what an amazing experience to even be there and do this. Incredible.

0:22:35

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, we felt lucky, for sure. And while we were there, we ran into researchers from. IISER Tirupati who were working on pika, mammoths and wolves and conversing. Yeah, they were like, oh, if you are going to use drones anyway, see if you can see burrows. And we could. So then, then we then had a follow up project where Shashank went back and mapped their barrows for pika, mammoths, and wolves. And now that data is being analyzed to see, what we can distinguish? Like, can we map their burrows? Can we see how that habitat is changing?

0:23:10

Lalitha Krishnan: I’m a bit wolf crazy. I might just tap into your resources.

I am really sad that you’re wrapping up operations for Technology for Wildlife foundation. Yeah, I am sad to hear and sad to say it even. But what happens to all the work, you know, all this incredible work you have been doing in the past few years?

0:23:37

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah, I mean, we are trying our best to document everything because that is actually our foremost concern also that we wouldn’t want work to be lost. I think the two things that I’m really pushing to be out there, one is that we’ve created, over this time, a pipeline of how we are using drones and drone data for scientific research and conservation. And all of this is done using like either very affordable or open access workflows and software. So, we are condensing the whole pipeline into videos and how to blog so that we can put it out there for anybody to use.

0:24:15

Nandini Mehrotra: So that, yeah, at least it’s there and hopefully it’s useful to more people. So that’s definitely one big part of it, along with codes and blog posts for almost every project and work that we’ve done. So that that stays on there on our website, as in.

0:24:29

Lalitha Krishnan: okay, so that will be up. You are not going to bring that website down.

0:24:37

Nandini Mehrotra: No, the website is going to stay up as an archive. And yeah, if there are any changes, I’m sure it’ll be updated there, but we will do that. And the other thing that will hopefully be up soon on that is an impact assessment, which I feel like is going to be for me, is important to be documented and put out there. One thing is just that so many projects happen generally with NGOs over time, scattered over regions and collaborators and years that sometimes it’s difficult to see it as a consolidated body of work.

0:25:09

Nandini Mehrotra: And I think for a field which can sometimes be disheartening, you know, people get jaded. I hope that seeing it as a consolidated piece of work in some way, know, at least show you what is possible to do, like what can be done if somebody decides to do some work, that is one thing. But also realistically, just the way funding models work generally, it’s not so easy as an organization to be able to put out…

0:25:44

Nandini Mehrotra: You know, I would not want to call them failures, but everybody tries different things in a space like this to have impact and some things work and some things. And while everybody can share very proudly what worked, they are not always in a position to be able to share what didn’t work so well as it should be. But right now, as we close operations, we are in a unique position where I think openly accepting things that may not have also worked or we may have thought worked, but somebody else assessing might think it could be better otherwise, like to be able to put that out for the whole ecosystem to be able, able to use. I think for me that is valuable. So, I’m also looking forward to like a third-party assessment, just compiling all the experiments that we have done over the last few years to be able to see what worked well, what was impactful, what will be better in the future, so that other people who are experimenting and working in the field, and even for us going forward, it gives some direction.

0:26:40

Lalitha Krishnan: That is inspiring and I think it’s very honest, you know, and bold to be able to do that. I mean, people can know what not to do if you put it out there and be inspired by everything else, you know, that you have done.

0:26:59

Nandini Mehrotra: Yeah.

0:27:00

Lalitha Krishnan: So, what for you, Nandani, is the legacy of Technology for Wildlife Foundation. What should it be remembered for?

0:27:09

Nandini Mehrotra: So, of course, our name, Technology for Wildlife, you know, it simplifies our mission and what we hope to have achieved in this time, just, you know, to do impactful work for the conservation of wildlife. And some of that will be innovation and impact. I mean, those are definitely things that want associates with us. But honestly, I do think tech and wildlife and conservation will continue.

If there is one thing about our legacy that I hope that we are remembered for, it’s that I hope that we remember that for using tech ethically and collaboratively, and to use it in a way that’s thoughtful for our planet, wildlife and also its people.- Nandini Mehrotra (Technology for Wildlife Foundation)

0:27:53

Nandini Mehrotra: So, for us, being able to be a bridge for some of those things was extremely valuable and a huge part of how we chose our projects and collaborators. We’re very aware that tech is an amazing gift and tool. It can also be used to exacerbate inequalities and differences. And we wanted to be able to work in a space that enabled more impactful grassroots action. So, I hope we are remembered for that.

0:28:32

Lalitha Krishnan: There are not many people or, you know, organizations ngos or otherwise that can say, “we’ve been ethical all along and we started doing the right thing and continue to do the right thing.” That is inspiring. And so, I just want to wish…

0:28:50

Nandini Mehrotra: To the best of our abilities. Sorry for cutting in. And I just went, like, I mean, at least I think, as per the best of our senses.

0:28:59

Lalitha Krishnan: Sure, sure. We are all human. Thank you so much, Anthony. This has been really great, and I wish you and all the your coworkers of Technology for Wildlife Foundation a great future.

0:29:15

Nandini Mehrotra: Thank you so much. It’s been really nice to speak with you.

0:29:19

Lalitha Krishnan: Take care.

Birdsong by hillside resident, the collared owlet.

All photos courtesy Technology for Wildlife Foundation

Podcast artwork by Lalitha Krishnan