With Mallika Ravikumar and Nishanth Srinivas

Episode #34 Heart of Conservation podcast. Show Notes (Edited)

0:03

Lalitha Krishnan: Hey there. I am Lalitha Krishna and you are listening to episode #34 of Heart of Conservation. Today I am speaking to two plant and tree lovers, basically tree experts. I find it so fascinating to listen to folks who are passionate and knowledgeable about the things that they love. Some of the fauna we are going to discuss are everyday plants and trees we pass by or sit under or love for their fruits and flowers, but truly we barely notice or know much about them. I promise you some extraordinary insights, botanical facts, myths, history, personal stories and more, on this episode.

0:47

My guest Mallika Ravikumar is a lawyer-turned-writer. She writes about history, culture and nature and has authored over six books mostly for children including one called ‘Tracing Roots’. She also has her own ‘YouTube’ channel called ‘Tree Talk with Mallika Ravikumar’. You’re very likely to have watched her on Instagram but you can check out more about her work on her website https://mallikaravikumar.com/

1:12

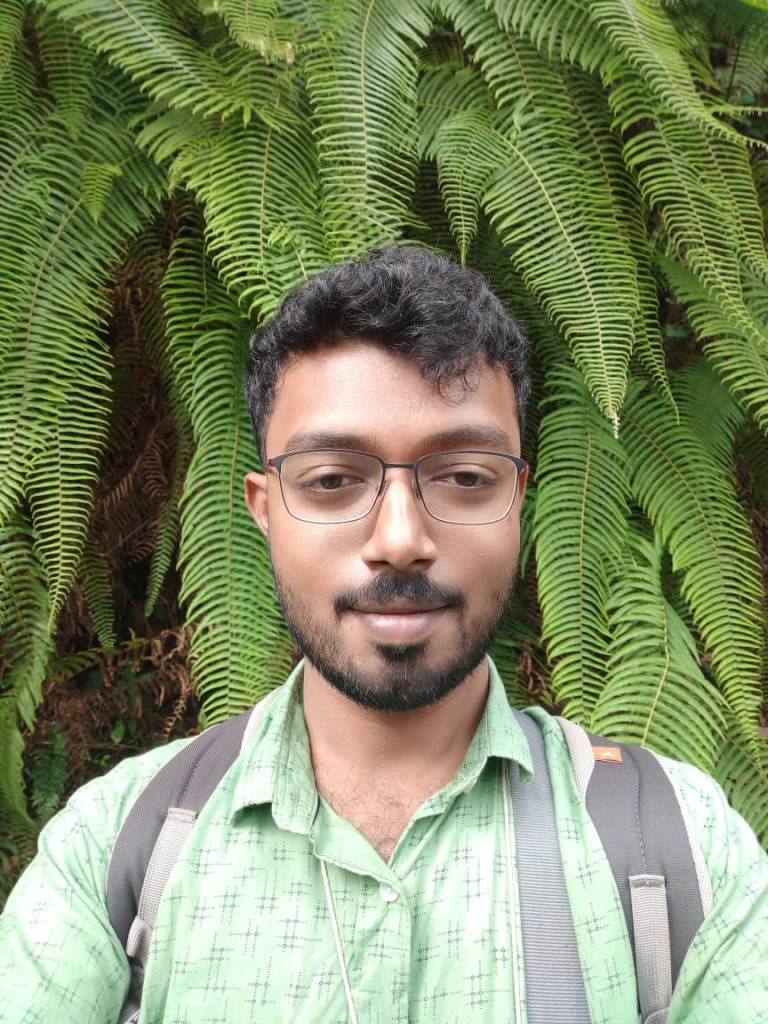

I have also been following ‘Trees of Shillong’ on Instagram which belongs to Nishanth Srinivas, my other guest. Nishant has a Master’s degree in Biotechnology from Bangalore University and worked as a Junior Research Fellow at the Department of Molecular Reproduction, Development and Genetics at the Indian Institute of Science. Having changed course, he is now based out of Shillong, and is working with an NGO called Conservation Initiatives. He specializes in satellite mapping and is interested in human–elephant interactions and landscape ecology. I believe Nishanth loves, doodling, graphic design, and writing and staring at tree canopies. I have a feeling that is true of both of my guests.

1:47

Mallika, and Nishanth thank you both for joining me on Heart of Conservation. I am really looking forward to your stories.

Mallika Ravikumar: Thank you, Lalitha for having me.

Nishanth Srinivas: Thank you so much for having us Lalitha.

2:02

Lalitha Krishnan: My pleasure really. To start with, why don’t you briefly tell me about the fascination for trees? Mallika, why don’t you go first?

2:12

Mallika Ravikumar: I grew up in Mumbai which as you know is a city with a lot of people, with a lot of concrete. Trees are not something you think about or associate with Mumbai. I grew up like any city person, knowing very little about trees and then I happened to shift into a place where I was surrounded by trees. I was very curious; I felt very bad that I didn’t know… I couldn’t recognize most of the trees around me. I didn’t know their names. It made me feel like something was off because I knew from what I had learnt in science and textbooks that we get our oxygen from trees. We get our food from trees. Trees are such an important part of regulating our environments so the role of trees in textbooks I was aware of, but I was not able to identify more than a handful of trees which made me feel very awkward. That started the process of making me want to learn, and enroll for field botany lessons during weekends at BNHS. I went for some field trips with botanists and ornithologists, to learn about birds and flowers and things. And, that took me down the rabbit hole and that learning process is still on. So, that’s how it all began.

Lalitha Krishnan: The learning process for all of us will keep going on I hope. What about you Nishanth?

3:31

Nishanth Srinivas: My story is not much different from what Mallika’s story is. I am also from the city; I am from Bangalore. Just like she mentioned, trees give us oxygen. I remember when I was so concerned about the environment, reading about all of this. The thing is during summer holidays, the best most outdoorsy thing that I would get to do is go to my grandparent’s place. They had a very big garden and they were every possible fruit tree there. This started my love for gardening. It started with gardening and I took a different route. I studied biotechnology and I happened to work in the Indian Institute of Science. And there, there were more trees and they have a 400-plus acre filled with trees. And, all my free time would be spent observing trees, canopies… Eventually, somewhere, that fueled my change to a different profession and now, I’m in conservation and I actually started observing trees beyond what is there in the city. And, that’s how Trees of Shillong was born and here we are. Right.

Lalitha Krishnan: It’s amazing how the ‘outdoors’ draws us out of our shelters. One of my podcast guests, Suniti Bhushan, introduced me to the concept, not his concept of ‘Nature Deficiency Syndrome’. Still, I would like to hear from you; why do you think tree stories are important? Nishanth, do you want to go first?

Nishanth Srinivas: Tree stories or stories in general related to myths or folk stories I believe are very important. Coming from a conservation point of view, whenever we approach a place or a region to understand what are people’s beliefs and how they connect with their culture, it usually starts with understanding or trying to make sense of their surroundings. And most of this is usually in the form of folk stories. There might be biases as conservationists so I try to bring in this idea of conservation a lot. And even in my stories when I write about Shillong, I usually end it with two lines about conservation which is very much the need of the hour. So, the thing is these stories need that. As a researcher and conservationist, they give me an understanding of the local context and how people relate to it and some sense of the relation of how they understand and make sense of the nature around them.

As a researcher and conservationist, they give me an understanding of the local context and how people relate to it and some sense of the relation of how they understand and make sense of the nature around them.

-Nishanth Srnivas

Lalitha Krishnan: So true. Mallika?

6:21

Mallika Ravikumar: Yes, very similar to what Nishanth said. In a country where we are such an ancient culture-we have such a plethora of stories and folk tales, myths, and legends about trees from various backgrounds: Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam… In every tradition, some people consider trees sacred. There is an association with them. I think, going into the psychology of it, people’s actions are not based on reason alone. Although we would like to believe we are rational, reasonable people, intelligence plays a very important role in how we behave but reason is only one of the faculties we use to make decisions. The other huge factor is emotion. Many things we do in our life–the decision to marry somebody, the decision to follow a certain career—it is based on hope and dreams and are also mixed with emotion. It’s not ‘reason’ alone that guides us. So, pummeling people with facts alone—you know, “trees give us oxygen, trees regulate the environment” — all this appeals to a certain side of us but all these legends, myths, folktales, and rituals and traditions; appeal to the emotional side of us. Which is also a very important part of human decision-making and psychology.

So, I think they have a very important role. Sometimes, I think emotions play a larger role when I connect with a tree or plant or pet dog emotionally, I feel much more to protect them and save them than if I connected with them academically or you know, intellectually. So, I think they play an important role in the way people behave in general.

8:05

Lalitha Krishnan: OK. And from a male point of view, Nishanth, do you also feel the emotional connection?

8:13

Nishanth Srinivas: Yes, very much so. The whole point of why we are very interested in learning and trying to talk about myths… is generally when we have a conservation or do a presentation, it’s to have that emotional connection. When we speak of myths and folk stories, they also reveal a lot about the culture and they trying to make sense so yes, the emotional aspect makes a very good point. It’s important.

8:33

Lalitha Krishnan: Thank you. This question is for both of you. So, how many trees are you going to share with us today? Mallika if you would like to start, you can tell us some interesting facts that you like and then a myth.

8:57

Mallika Ravikumar: Sure, how many trees? There is no answer to that. It can go on endlessly but I would be happy to start with a tree that I talk about a lot which is the teak tree which is an Indian tree. It’s called ‘Saagaun’ in Hindi, and Thekku maram’ in the south. In fact, the word ‘Teak’ itself comes from the word Thekku maram’ which is in Malayalam, and before that in Tamil. It is a tree that changed world history. We have this human-centric way of looking at history and saying, “This king changed history, this general, Alexander the Great, Akbar the Great, Chandra Gupta Maurya; they did this…and they changed history…” But really, so many of these trees if they could speak, would tell you that they are the ones who changed history and changed the course of time. So, teak is one of those trees you know.

But really, so many of these trees if they could speak, would tell you that they are the ones who changed history and changed the course of time. So, teak is one of those trees you know.

-Mallika Ravikumar

9:45

There is this period in history in the 16th and 17th centuries that was called the period of Teak Rush, which was a time when the French and the British were engaged in several battles before and during Napolean’s time when the British were very wary of the rise of Napolean because he was a big threat. And, they had completely decimated the oak trees of England to build ships. And we all know the British were able to control a large part of the world because they had a great navy. And what was the basis of their navy? Their ships. And what were their ships made of? Wood. But their oak forests were completely decimated because of the ships they had built in conquering various places and they were on the lookout for wood to build their ships. That is when this period of Teak Rush comes in when both the French and the British are on the lookout for wood for building ships. Because all these battles that used to happen were naval battles. And by chance, it is the British who discovered the teak forests of southern India and then they brought in forest laws to control all our forests. The conservation laws that we have today didn’t start as a measure of protecting the forest as much as wanting to control the resources from the forest.

And what is the main resource they wanted to control? Teak. They had scouts going out to look out for these teak forests. They massacred these forests, they had teak plantations, they converted large forest areas into monoculture teak plantations and it is the teak that they got that helped them get this hegemony and control larger parts of the world. So, it titled the scale of history. We are having this conversation in English today because of teak otherwise we might have been talking in French. Who knows? But it’s teak that changed the tide that was the bedrock of the British empire. So, that’s just one of the many stories that changed our past and continue to shape our present.

11:37

Lalitha Krishnan: That’s amazing. Frankly, I did not know of this. I have only heard of the Gold Rush, not the Teak Rush. Nishanth, what plant, or tree are you bringing home to our listeners?

11:41

Nishanth Srinivas: Well, I thought of four plants but one tree which is very common to our listeners which we all know; it is very common is the coconut. I have always been intrigued; there was a coconut tree near my home in Bangalore, in my neighbour’s house and it stood tall. In 2018 we had very terrible rains; very cyclonic. There were a couple of trees which fell but this one tree did not fall. You do not hear of many instances of coconut trees falling and if you follow the weather channels you will always see that when they talk about coasts or rain in the weather reports, you will always see some palm trees flaying around but it’s not usually uprooting away. I always used to think about why and it is very interesting how coconut trees have adapted to live in a coastal region where geographically, it is quite flat. We know that when the winds come in, they pick up rain, and the first thing they will encounter is the coast. So, how these trees have adapted is quite interesting.

13:00

First of all, the shape of a coconut tree is a tube-like any other palm tree. And if you observe the bottom of the tree, it is a little wider at the bottom than the top. Very marginally. And, the top region of the tree, the crown as we call it is quite flexible. That is one. We have all seen Bahubali (the movie) where he uses the palm tree to make it so flexible that it is wind-borne and things like that. Though, palm trees are not that flexible but the top region is. So, it sways when there is a lot of wind movement. That is one.

13:39

When we talk about the inside structure of the coconut tree… it is a monocot. Monocot trees do not grow by girth every year and it’s made up of spongy tissue inside. It is so much like a concrete mould and is reinforced by lignin fibres. These fibres run longitudinally along the length of the coconut trees so they are fill which is inside the concrete. It provides structural stability to the tree. That is one.

14:11

The other is the roots. We have all seen the roots. These roots are fibrous. They go in every direction and they hold the tree in a place like any other (root system).

14:25

Last but not the least is the frond. So, the coconut tree is almost feather-like; it is pinnate. So, it has a central big stem called the Rachis. So, most of the very tall palm trees have feather-like leaves. So, these are some of the very interesting adaptions that I came across when I was trying to understand how the coconut tree stands cyclones.

14:51

Lalitha Krishnan: Wow. You explained that well. I also believe every part of the coconut tree can be used. Am I right?

15:00

Nishanth Srinivas: That’s true. That’s one of the reasons why it is called ‘Kalpavriksha’ I guess. Mallika would have many more stories about it. But interestingly, since coconut trees are there in the tropical regions all around, there are multiple stories of ‘how’ or ‘what’ when it comes to the folk stories. Each culture or region has its own take on it. It is quite interesting.

15:25

Lalitha Krishnan: O.K. Would you like to share that?

15:30

Nishanth Srinivas: I will quickly share two of them. One of them is from Hindu mythology itself. When Ganesh was very small, he wanted to play with the third eye of Shiva. And then, I guess, one of the demons if I am not mistaken a small model/idol with three eyes and gives it to Ganesh. By mistake, this small idol falls from Ganesh’s hands and falls on earth. They say that’s how coconut came into existence or how mankind found the coconut.

16:04

That is one of the stories. There is one more very interesting story—again similar to this—the three eyes. When you de-husk a coconut, why does it have three eyes? This story is from the Polynesian culture- Hawaii, Melanesia, New Zealand and all of those places. They say, in an ancient island there used to be a chieftain’s daughter. Her name was Sina. She used to always visit the sea and she sort of became friends with an eel. This eel over time developed feelings for Sina. And it became very violent as time moved on; wanting more of her time and affection. But then, she goes back to her village and complains about this eel which is sort of always stalking her. And then, one of her relatives goes and kills the eel. Before dying, the eel’s head speaks. It tells Sina to bury the head in the sand and that it will be reborn as a tree whose fruit Sina can drink. The three holes are where the coconut shell is the lightest. So, every time, you break it open and drink, it’s like the eel kissing Sina. That’s what the story says. These are different stories and they talk about (lost in translation).

17:30

Lalitha Krishnan: Lovely stories. Mallika, would you like to share another one?

17:33

Mallika Ravikumar: Sure, I can talk about a plant which is not a tree but a lot of people think it is a tree which is the Banana. You know, in usual parlance, we say banana tree or kela ka jaad or vāḻai maram in Tamil. Botanically, it is not a tree and the reason is- for a plant to be considered a tree, the key feature is the wooden trunk. And the banana, if you notice closely, does not have a wooden trunk so it is not botanically a tree, although we all call it a tree.

Botanically, it is not a tree and the reason is- for a plant to be considered a tree, the key feature is the wooden trunk. And the banana, if you notice closely, does not have a wooden trunk so it is not botanically a tree, although we all call it a tree.

-Mallika Ravikumar

18:03

There’s this interesting story from the Gadabas tribe of Odisha which I like very much. So, the story goes that there were five sisters. They were the mango, the tamarind, the fig, the jamun and the banana. As they were growing older, their father was getting worried that they weren’t getting married and he wanted to find husbands for each of them. So, he asked them what kind of husbands they wanted and they all told him. And, he looked for such partners for them but the banana said, “I want children but I don’t want a husband.” This is a very modern, feminist sort of story so I like it for many reasons. She said, “I want children but I am very clear I don’t want a husband.” So, the father grew worried. “How is this going to work?” But the other girls got married and they had children and it is said that all the mango and fig, tamarind and jamun trees that we have are descendants of those children. But then what about the banana? She said, “I don’t want to marry but I want children.”

19:00

The thing is as per the story the banana had children without a husband. The beautiful thing about this story is that bananas reproduce parthenogenetically which is asexual reproduction. In botanical terms, if one were to study that there are two forms of reproduction: one is sexual, and one is asexual; the way the banana reproduces by bypassing the fertilization of the ovule by the pollen is sexual reproduction. And it is fascinating to see that this ancient folktale has captured that in such a simple way. Those daughters wanting to marry and one daughter saying, “I want children but I don’t want a husband.” And to see that very astute scientific observation finds reflection in this folktale. So, I find it very fascinating for many reasons including the fact that it’s a sort of modern, feminist sort of take on life. But, yeah, this is a fascinating story about the banana that I shared on my YouTube channel where I share these sorts of stories that I find.

20:02

Lalitha Krishnan: Fascinating. I agree with you. How on earth did they figure it out then? Nishanth, it’s your turn. Another tree, another plant?

20:10

Nishanth Srinivas: One more tree that is quite common in Bangalore gardens is Nyctanthes arbor-tristis. It’s called parijata. It’s also called night jasmine though it does not belong to the Jasmine family. Again, according to legend, what happens is this tree also comes from the churning of the milky ocean. The demons and the gods churn up the mountain. And then, from the ocean arises this tree and Indraloka who plants it in his garden. Once, Narada,–who is usually a mischief-monger—takes some of the flowers from Indira’s garden and gives them to Krishna. And, Krishna goes and gives it to Rukmini, his wife. Having known this Narada being Narada, he goes and tells Krishna’s other wife, Satyabhama, that Rukmini got these heavenly flowers and Satyabhama becomes quite jealous. So then, she asks for the whole tree and so Krishna goes and steals the tree. En route, when he is coming with the tree, he is confronted by Indra and a battle ensues. Eventually what happens is Indra curses the tree such that it never produces fruit. Interestingly, this parijata does not produce fruit. It belongs to the Oleaceae family. It produces a heart-shaped capsule. Oleaceae is the olive family- the olive fruit. So, this does not produce that. It just produces the capsule. And, this is a little bit of humour: he (Indra) says that the owners where this plant is will never get the flowers. What I have observed is that in Bangalore morning time, around 6:00 or 7:00 o’clock, you see all these people coming to pick these flowers and usually the flower never falls in the garden where it is planted but usually falls on the roadside. ( lost in translation )These are some of the things that I find nice. Also, it brings the thought –as we discussed- we don’t know what came first. This or that but it is people trying to make sense of what they observe in nature and putting it into some sort of context.

22:55

Lalitha Krishnan: Very interesting. I can relate to this. I never get any of the fruits or flowers that I plant. They all go mostly to the monkeys. But I don’t feel cursed. I feel privileged. I think it’s the tax one pays for having wildlife around. Mallika, what next?

22:17

Mallika Ravikumar: The story that Nishanth related…I had a parijat growing in my house and it was exactly like that. The plant was on one side of the fence and the flowers were falling on the building on the other side of the fence. That story also has another element. You know when he brings back the tree, Rukmani is very upset and says, “Why did you give Satyabhama the tree?” So, Krishna being very smart, plants it in a way that Satyabhama is happy to have the tree but the flowers come to Rukmani’s side of the garden because he knew that then both his wives were happy. These folk stories have several narratives or variations. So, that’s also very interesting that someone has heard one part and you hear another part. This is a version of the story that I had heard but yes, it’s a beautiful tree and flowers and a lovely story also.

These folk stories have several narratives or variations. So, that’s also very interesting that someone has heard one part and you hear another part.

– Mallika Ravikumar

24:12

Another tree with lovely flowers that I can think of is the silk cotton tree- the semal. This story comes from the Mahabharat. This story is narrated by Bhishma when he is on his bed of arrows; when he is about to die all the others come around him, asking for advice and ask various questions. He narrates this story when he is asked about the qualities of a good king. How must a king behave when a neighbouring king is stronger than him? What is the diplomacy and relations one must have? So, he narrates this story of the silk cotton tree.

Nishanth mentioned Narada so this story struck me. Narad Muni, as he said was a troublemaker. He is walking along a forest and he comes upon this beautiful silk cotton tree and he is absolutely stunned. He says, “You know, you are so gorgeous and your flowers are so beautiful, how is it that you are still standing like this? “The wind is blowing so hard over here; all the trees are bent; all the leaves have fallen because Vayu has blown with such force but you seem to be unaffected by Vayu’s force. How is it possible? So, the silk cotton replies saying, “You know Vayu may be strong for the others but I am stronger than Vayu and what do you think? I can’t bear the brunt of the breeze?” So, he boasts about how strong he is and Narada is sure that if the wind really wants to blow something down, nobody can stand in its way so he being a troublemaker, goes back to Vayu and says, “ You know there is this proud silk cotton tree in the forest who thinks it is stronger than you and I find it laughable.”

Vayu of course says, “That’s ridiculous. I spared the silk cotton tree because when Brahma created the world, he rested under this tree and therefore, I have respect for this tree and therefore I don’t blow on it. But, if the silk cotton tree is going to interpret this as my weakness, let me show him how strong I am.

26:04

He says, “I’ll show him how strong I am tomorrow. But that night, the silk cotton thinks and reflects and looks at all the trees around and thinks, “If all these trees are bent and turned over, and leaves have fallen and they are all facing Vayu’s impact, surely it can’t be that I am so strong that I am stronger than Vayu.” So that night, the silk cotton tree decides that before Vayu comes, let me myself, drop my leaves and flowers so that when Vayu comes tomorrow, he cannot inflict any damage on me. So, the next day, when Vayu comes blowing fiercely down the mountainside, the silk cotton has nothing left. No leaves or flowers. Nothing is left on the branches. He says, “I am glad that you learnt the lesson to be humble. Now shorn out of your beauty, you have realized that you don’t need to show off many times. People are being gracious and nice to you and it’s not all about how strong you are.” So Bhisma is narrating this story to say that you have to accept that someone is stronger than you and not be futile and say, “I can take on anyone.” If your neighbouring king is stronger than you, then accept and be humble and bow before him. That was the context of the story.

27:17

But I use this story when I take children out for tree walks to tell them about leaves falling. And, why some trees are deciduous and some trees are evergreen and have you noticed leaves falling? So, if you just start off with deciduous and evergreen, kids sort of get put off. But if you start with a story, it becomes a point of generating curiosity and then they start noticing which trees around them are dropping leaves. Some kids have come back to me and said, “Aunty, we remembered this story from the Mahabharat when you told us when we saw this tree outside our school which was dropping leaves. So the important thing is also to connect kids with trees around them because it’s a way to generate curiosity.

27:56

Lalitha Krishnan: wonderful. I am feeling like a kid listening to your stories. Nishanth, why don’t you tell us more? What’s your next tree or plant of choice?

28:08

Nishanth Srinivas: The next is a plant, a type of ginger and this takes forward what Mallika said. Some of these stories and myths also serve a purpose to teach kids or the younger generation something. There is some moral behind it. This story is about a type of rock ginger. Rock gingers have very showy flowers and they are quite common in the Himalayan region. It’s called butterfly-ginger, butterfly rock ginger- it’s got different names but they have very showy flowers and they are quite common in and around the Himalayan region. This particular plant, its scientific name is Hedychium gardenarium.

Since I work in Meghalaya, this is one story which came to me from one of the museums that I visited here. So, they have this plant and they have this story along with it. so, in Khasi, this plant is called Ka tiew lalyngi. ‘Lalyngi’ which I understand must be the name and ‘tiew’ is flower. There is a saying, “Wat long tiew lalyngi pepshad” which roughly translates to: “Do not be late like the Lalyngi flower who missed the dance.”

29: 31

So, the story goes that there was a great feast. There was a huge tree called the lei tree. I am sure I am pronouncing these things wrong but if someone knows the correct pronunciation, please get back to me. This large tree was blocking out the sunlight and that itself is a different story. Eventually what happens is that people cut it down and there is sunlight again in the land and there is a celebration that happens. So, to celebrate, all the creatures that is animals, people, birds, and insects were invited to a great dance in the region of Meghalaya. So, what happens is there’s also this girl who is invited. Her name is Lalyngi. She’s a very beautiful young girl and she happens to come. But the thing is she wants to look the best. What she does is she takes a lot of time to get ready. In that process of getting reading, she loses track of time. So, by the time, she reaches the dance arena, she finds the event is already over and she is quite upset by it. Because nobody is there to see her after all the effort she took. She is so upset she jumps off the cliff and dies. Where she dies, a flower is born and that flower is the Hedychium gardenarium.

The thing is, this flower is so much part of the culture. If you have seen the Khasi dress, they wear these Paila beads which are mostly in shades of golden yellow and red. And, this flower has stamens which are of the same hue of red. And the petals are yellow. In some sense, they feel it is part of their folk story. Most of these stories are oral; part of the oral tradition they have here in Meghalaya. Stories that are passed on through generations; something which they feel is one of their own which tells something about their culture. And, interprets some sort of moral lesson to children to prioritize and give importance to things when they are doing something.

Stories that are passed on through generations; something which they feel is one of their own which tells something about their culture. And, interprets some sort of moral lesson to children to prioritize and give importance to things when they are doing something.

-Niahanth Srinivas

32:12

Lalitha Krishnan: Wow. That’s a sad but beautiful story but also such an exotic flower.

32:21

Nishanth Srinivas: It is. Google it and see.

32:28

Lalitha Krishnan: Mallika, would you like to share another story or plant if you like?

32:33

Mallika Ravikumar: Another commonly seen tree in India is the Neem. This is not a story that comes from myths or folk legends. It’s a historical, current affairs kind of story. Where, as we all know, the neem has been traditional medicine in India for centuries. From ancient times to now, we have all experienced how if you had chickenpox, were told to have a bath in neem-leaf water or brush yourself with neem branches to heal.

33:10

Generally, if there’s a neem tree around you, one considers mosquitoes won’t come into your house. Neem is just part of growing up in India. You keep hearing the healing properties of neem. Some decades ago, in the US this company was granted a patent for the use of the neem in their pesticides or herbicides for controlling pests in plants. And, they also applied for a patent in the European patent office and fortunately, this was highlighted and India opposed that. The Indian Council of Scientific Research opposed that and this is Traditional Knowledge. A patent as we all know is a special right given to you if you have invested in researching something and you have come up with something very novel, and it is original and it’s of use to people. Those are the considerations for a patent. But here is someone asking for a patent for something that was commonly known. Haldi is another one. Basmati, as we know, we also got a patent some time back. So many Indian plants, some of them medicinal whose healing properties have been common knowledge—even illiterate, uneducated—everybody in India knows about the healing properties of these plants. You don’t need to be a doctor or anything.

34:17

And, you get a patent for that where you are claiming that you have something original and useful and novel was something that India opposed and that patent was finally revoked after a lot of appeals and several processes. What it highlighted was something called Biopiracy. Piracy we know that if you film a movie in a theatre and you release it and make money out of it, is called a pirated copy of the movie or a book. Because it is making money out of somebody else’s creativity without giving them their due.

34:50

But, this idea of bio-piracy became a taking point after this Indian Neem incident of biopiracy and India then woke up to the fact—even till now, several of the patent applications made by pharmaceutical companies in the West are based on traditional knowledge of ancient cultures including India. And then fortunately this was taken to serious levels. There was this body called the Indian Traditional Knowledge Systems and a database was formed where if someone in the US applies for a patent for, let’s say haldi, obviously they might know this is traditional knowledge in India… But the Patent Office can then search in this database where you have all these plants that have been recorded as traditional healing plants in unani, ayurveda, siddha etc. and it will show up in the search at the patent office. At least in the future, private enterprises will not given rights– exclusive rights—for traditional healing plants of common knowledge in India. It all began with the neem biopiracy case that triggered all this. That’s not a legend or a myth but an interesting story, especially something to be aware of this is a huge amount of traditional knowledge that we are sitting on and some people are using it for private gain. We should be aware of it.

36:14

Lalitha Krishnan: Very true. And biopiracy is a new one for me. And I doubt they are trying to get patents for anything innocently.

36:28

Mallika Ravikumar: Absolutely. There was a very interesting article that I read. In Covid times, a lot of plants were getting stolen out of our botanical gardens. Orchids. Nishanth is in the north-east. He will know better. Orchids are disappearing in the northeast. Some of them are threatened species because there is this craze for owning these exotic plants and keeping them in your gardens and your house. The West has always had this craze but even today it is there. We talk about the tiger and the elephants and big mammals, birds etc. when they are threatened but a large number of species on the IUCN list are actually plants. Many of them are Indian plants. We somehow don’t highlight them because they are not as dramatic as the tiger and elephant and so on. But they are also part of threatened species.

We talk about the tiger and the elephants and big mammals, birds etc. when they are threatened but a large number of species on the IUCN list are actually plants.

-Mallika Ravikumar

37:14

Lalitha Krishnan: Butterflies too…from the northeast. Thanks for sharing that, Mallika. Nishanth, would you share some more?

37:21

Nishanth Srinivas: Yes. Mallika has given me segways into different things… She mentions the US and how plants are collected and taken to different places. One very common plant which was reversed from the New World to the Old World is scientifically known as Euphorbia pulcherrima. It’scommonly known as the Christmas flower. It’s these red bracts; it’s almost like bougainvillaea. It usually flowers during Christmas time. I’m sure both of you are familiar with seeing this plant. It’s very common. Especially in the western ghats, it’s grown as a hedge around coffee plantations etc. Here in Shillong, it’s quite a common garden plant.

38:14

Though this plant is a showy ornamental plant, it’s got a very nice and interesting story. And, it highlights something which I shall share at the end. It’s also commonly known as the poinsettia. The thing is even the names: Why poinsettia? Why Christmas flowers? It has a nice big story to it. This plant is native to the dry forests of Mexico, basically central and northern South America.

38:50

During the Aztec civilization time, this was also a plant of high cultural importance. In Aztec, it was known as cuetlaxochitl which translates to ‘a mortal flower that perishes and withers but is all pure. Apparently, in Aztec legend when it was formed it was white. And, because of the war between two different tribes, the flowers become red.

39: 26

So, the Aztecs would plant this around their habitations or wherever they had their cities and stuff. But we know a little bit about their history and how the Europeans started coming and colonizing the West. So, what happens is, that when the people/missionaries came into the region in the 17th century, they noticed these plants. They sort of took this aspect of how important this plant was and made it part of the Christian culture. How they did this is quite interesting.

40:10

There is one interesting story. In Spanish, this flower is called Flor de Nochebuena which translates to “flower of the Christmas eve.’ The story is all about a girl named Pepita. I am sure you’ll be aware that during Christmas time, they make a manger which is a model of the birth of Jesus/ nativity scene. This girl comes from a very modest background. The story goes that all the people go to the church to offer something to baby Jesus. Everybody is trying to get the best thing to give as an offering. Being of a modest background, she tries her hand at many things. She tries to knit a shawl but she can’t untangle the wool. She then tries to make small boots for baby Jesus but she doesn’t even have the strength to push the needle through the leather.

41:29

She gets quite upset and a stranger comes up to her and tells the young Pepita, “Even if you offer anything with a lot of devotion, it will be accepted.” So, she goes around and gathers a bunch of leaves and twigs and she offers them at the church. What happens is, magically over time, these greens she has picked, turn red. This also goes back to the plant as I was saying. They are not flowers but like bougainvillea, they are red bracts. The flowers themselves are quite small. The story weaves the aspect of those and also them coming into flower during winter time around Christmas. That is what I found interesting; it gives a reference point. Some of these myths and stories may stay but this is how some aspects get introduced and become one of their own. So, that was what this story represents to me.

42:45

The word ‘poinsettia’ is also quite interesting. Mallika mentioned how people collect plants. There was a person called Joel Roberts Poinsett who was very much into collecting plants. He was from the US and was working as an ambassador to Mexico sometime in the early 19Th century. When he was there he collected these plants and sent them to the botanical gardens. In honour of him having introduced this to the western plant per se, it got the name, poinsettia. In political terminology, there is a term called poinsettismo which represents a kind of diplomacy which the US follows. Which is very intrusive. It represents how the US is or functions with other countries which they trade with. This tells us also how words are derived, how there are stories are attached to them and what the roots of the stories are. This is an example of a plant being behind one such name.

44:09

Lalitha Krishnan: Thank you.

44:19

Mallika Ravikumar: I was about to say, I learnt a new word. Poinsettismo. I am going to look it up and read more about it.

44: 27

Lalitha Krishnan: The association is still there. I remember 2 Christmases ago; I gifted a poinsettia to someone.

44:36

Nishanth Srinivas: It all came from one small town in Mexico and got sent to the Philadelphia Botanical Society and from there, if I am not mistaken, just one company had world domination. And, they sent this poinsettia to different parts of the world. So, all of them probably have one or two mother plants if I am not mistaken. That’s how it is.

45:09

Lalitha Krishnan: Thank you so much. My last question to you both—and I feel almost guilty asking you this question—because both of you have already introduced so many new concepts and words but I am going to ask anyway cos this is how I always end my podcast.

Could you share something about trees or plants that is new to us or significant to you in some way? It could even be about your relationship with plants.

43:35

Mallika Ravikumar: Before that, can I add to something that Nishanth said which reminded me of something else?

45:40

Lalitha Krishnan: Of course:

45: 42

Mallika Ravikumar: Nishanth said how beautifully the idea was told to the girl: “You offer something with devotion and that is the most important thing”. There is a mirror story of that even here. That is one of the stories that I thought I could narrate but we don’t have time. This is the popular story of Shabri and the ber—the Indian jujube—where you have, shabri picking ber fruits from the tree and offering them to Ram. It comes from the Odhiya Ramayan. It’s not in Valmiki’s Ramayan. And, that became a very important story in the Bhakti movement to cut across barriers of caste and varna… In the Odhiya Ramayan, he accepts this jhutey ber as they say. She has tasted the ber, tasted the fruit to see if they are sweet and gives it to Ram. Laxman says, “I cannot eat this but Ram says, “Anything offered to me with love and devotion is acceptable and nobody is small or lesser or greater and I will take anything that is given to me with love and devotion. That is exactly the mirror story of what he mentioned. So, in every country, or culture, I guess you have such stories and it is really beautiful to study these parallels. Even in the Bhagvat Geeta, you have a slok/verse which is exactly that. “Patram pushpam phalam toyam, yo me bhaktya prayaschati” (You offer me fruit, you offer me flowers, you give me anything. As long as you give it with devotion, I will take it.)

It’s beautiful though and very often those offerings are plants and fruits and flowers which is a form of expressing devotion to whichever divine power that you worship.

47:16

Lalitha Krishnan: I am getting goosebumps. Between you guys, you can start an Oral History of Plants podcast. There are too many stories to go on one episode.

47:30

Nishanth Srinivas: There are a lot more.

47:31

Lalitha Krishnan: I think it will be amazing to have an encyclopedia of stories. So, coming back to my question…

47:45

Nishanth Srinivas: One word which comes to mind and which is central to… the reason why I am here also is ‘Green blindness’. People do not see green things. What captures our imagination is things which move—animals, birds, insects. They come to mind very fast but when we talk about plants, a common person may speak of plants in respect of their utility. In respect to food, or in respect to being ornament like a flower. But plants are much more. They are the reason why we are here. Somewhere when it comes to the topic of conservation, as Mallika initially spoke of the British way of forest management, it’s mostly utilitarian purpose. They wanted something which they wanted to extract and that is something which is continuing even today. Even with many forest departments, there have been many instances of people razing down natural forests, razing down places of high diversity and putting down monocultures of teak and mahogany and things like that. There are many examples like that that keep happening. With different forest laws and policies and amendments; time is progressing least in the Indian context, what is happening is not going for the good. In some ways, it is going for the bad because we are also an aspiring nation. We want to develop and be a superpower. We always see this happening in the spectrum of life but the conservation of our natural resources, our trees, what is natural per se, is much more important. Usually, the first thing that gets chopped or which gets the axe is always the tree. When there is any development even in our cities, when there is road broadening or widening, or setting up an economic zone or trying to expand business, anything that relates to land, it is usually the plants and trees which suffer first. Because they can’t move. They will be lost if they are removed from a region.

Usually, the first thing that gets chopped or which gets the axe is always the tree. When there is any development even in our cities, when there is road broadening or widening, or setting up an economic zone or trying to expand business, anything that relates to land, it is usually the plants and trees which suffer first. Because they can’t move. They will be lost if they are removed from a region.

-Nishanth Srinivas

50:40

Green Blindness is also one of the reasons why I started writing about plants though I do not come from a background of botany. So, that is something that I believe people should keep in mind and be more cognizant of what is green around them and living.

50:55

Lalitha Krishnan: So true. And where can we read your writings?

50:59

Nishanth Srinivas: I’m on Instagram @treesofshillong Otherwise, very much like you, write for magazines like #RoundGlassSustain I saw you had an article about how ants carry flowers so… different things. I also write to the Meghalayan. I have been writing about plants: myths and trees that are very common in Shillong gardens.

51:36

Lalitha Krishnan: Do share these links for my blog. Okay, Mallika; what would you like to share?

51:43

Mallika Ravikumar: Okay. While there are many ideas and words, something I noticed before I started learning about trees, I noticed that when I used to walk, I used to like looking up at the canopies of the trees from below and the reflection and the play of light. I discovered much later, that there is a word in Japanese, for this phenomenon and it is called Komorebi. I was so happy to discover that there was a word for this. Because, sometimes you observe or have certain experiences and you don’t have a word to explain what it is you are experiencing. But I was delighted to know that there was a word for this light filtering through the canopy of trees and the way you see it from below is called Komorebi in Japanese. So that’s a very wonderful idea and concept.

52:31

And going from that, another associated term called ‘crown shyness’. What is fascinating is—again when I tell children or tell adults about it—if you’re walking below trees—say on the road and there are trees on both sides of the road, if you look up, you will notice the canopy of the trees are meeting up but just about. They touch each other but there is a slight gap between them. Not all trees do this but it is observed in many places and this is called ‘crown shyness’ where the crowns of the trees just stay within touching distance of each other. The reason of course is because they both want sunlight and if one covers the other one, the other one is not going to get sunlight. So, the tree is not going to grow under the shade of the other. There is a reason of course for it but we call it “crown shyness’ and it is very easy to observe when you’re out for a walk. Just look up. There are two beautiful things you can see. Light -whether daylight or moonlight –whatever it is, it’s filtering through these trees and it’s a beautiful Japanese word called Komorebi and this concept of crown shyness which you notice. It almost looks like the trees are having a conversation but they don’t want to be touching each other they are just about touching. That’s a beautiful thing to see and anybody can observe that when they are walking under trees.

53:46

Lalitha Krishnan: It’s like they are being good neighbours, right? Not getting into each other’s space that much.

53:53

Mallika Ravikumar: Live and let live…

53:55

Lalitha Krishnan: Exactly. And the Japanese word? Is it the same for forest bathing?

54:00

Mallika Ravikumar: No, Shinrin-yoku I think. Forest bathing is where you soak in the sounds smells and sights of a forest, and you spend time there. That is also a very beautiful Japanese idea as well. But this is Komorebi which is light filtering in through the canopy, through the leaves. The leaves are moving in the breeze, so the light is playing and dancing around. That idea is called Komorebi. It is also very beautiful to have a word for it.

54:25

Lalitha Krishnan: It paints such a pretty picture. That’s fantastic. Thank you both so much. It was wonderful

54:35

Mallika Ravikumar: it was wonderful being here and chatting and connecting with Nishanth and you; both of you.

54:37

Nishanth Srinivas: Yes, same here. It was very nice to hear about new things and learn and put forth…

Disclaimer: Views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the podcast and show notes belong solely to the guest/guests featured in the episode, and not necessarily to the host of this podcast/blog or the guest’s employer, organization, committee or other group or individual