Heart of Conservation Podcast Episode #39 Show notes (Edited)

00:06

Lalitha Krishnan:

Hi, I’m Lalitha Krishnan and you’re listening to episode #39 of Heart of Conservation. I bring you stories from the wild that keep us all connected with our natural world. You can read the transcript for this podcast on my blog, Earthy Matters.

00:21

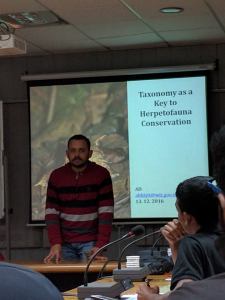

I’m speaking with Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed. He’s a journalist at Frontline magazine. He has degrees in history from JNU -New Delhi and the University of Oxford. I first met Vikhar at the Wildlife Institute of India in 2016, where we attended a course for nature enthusiasts.

00:40

Vikhar considers himself more of a political and social writer, though he has written some wonderful nature conservation articles that are well researched and fascinating to read. We are going to discuss some of those today as great examples of ethical writing for conservation. In a time where short snippets of fake or sensational news draws more attention, I consider Vikhar a rare breed of journalist. I admire his no-nonsense style in the long form, written with the eloquence of the seasoned journalist that he is.

01:15

Vikhar, welcome to Heart of Conservation. I’m so grateful that you made the time between your travel and work to speak with me.

1:20:

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Thank you so much, Lalitha, for being so patient with me while I’ve been travelling these past few weeks. And as I mentioned earlier, most of my work has been on the politics of Karnataka and social issues, rural affairs. I have a very diversified portfolio of work. Since we met in 2016, I’ve tried to sort of also work on issues of conservation through my journalism.

01:53

It’s not easy to report on issues of wildlife, human-animal conflict, but because of the long form that Frontline allows me to use and because it gives me time, I’ve sort of written a few good articles so I’m happy to chat with with you about these.

2:15

Lalitha Krishnan: Thank you so much it’s been worth the wait. You have as you said published a great many stories and one of them is about Kenneth Douglas Stewart Anderson the Scotsman who was born in India. He is considered a pioneer of wildlife conservation in southern India. But unlike Corbett, little is known about Kenneth Anderson. Would you like to tell us something about him?

02:43

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Lalitha, growing up in Bangalore, and you know, when I was a child, I used to read a lot. And at some point, I came across the works of Jim Corbett. And later, I think, if I recall now, I was in college when I first encountered the works of Kenneth Anderson, which resonated far more with me because I learnt that he lived in Bangalore and he would often foray into the forests around Bangalore. And initially my fascination was like, “Oh my God, wow, these were all forests?” I visit these places now and they are part of the sprawl of urban Bangalore.

03:27

And even further on, what were forests once upon a time are now towns. So that was my fascination. And then he was such an eloquent writer and the adventure. When I was young, I primarily used to engage with the works of Kenneth Anderson because of the adventurous element in them. I found that fascinating how he would go and track these man-eating large carnivores such as tigers and leopards and bears and elephants as well at times and he’d write so mellifluously about these encounters. So that was the thrill and then later when I became a journalist, I used to meet a wide variety of people.

04:18

And then a seed of doubt was sowed in my mind when someone casually mentioned, you know, I mean, “You love Kenneth Anderson, but have you ever considered the possibility that he was fibbing, that he was perhaps exaggerating?” So that casual comment made me think more deeply about his work.

04:44

And I wrote a rather detailed article. The primary motivation was to examine the claim of whether he had actually shot all these tigers and other animals that he wrote about or whether he was exaggerating. So through the course of writing the article, I learned a little bit about him.

05:05

So I learnt that he was born somewhere near Hyderabad in 1910 and then shifted along with his family at some point to Bangalore where he lived in the heart of Bangalore. Right now, the place where he lived would be unrecognizable but it was very close to Cubbon Park and he died in 1974.

05:31

You described him as a Scotsman but to add a bit I think he described himself–he was aware that he was an Anglo Indian because his family had been resident in India for several generations. That is one thing that is important perhaps. Also, among the many books that he wrote, he wrote a work of fiction set around the Anglo-Indian community in India. This had this had nothing to do with animals. So this just as a tidbit And then he worked in Hindustan Aeronautics Limited.

06:16

And often he had a wide network of informants in the villages around Bangalore and what is now Tamil Nadu also. At some point he would hear stories or reports of marauding wild animals, he would set off in his trusted Studebaker… I don’t know how you pronounce the name of that car, but he mentions it often in his writings. And then he would go and he’d write sort of very detailed reports of tracking these animals and then shooting them. And, you may also be interested to know what was the result of my sort of delayed investigation, right?

07:10

I set out to examine the claim whether he actually shot these animals as he claimed. The result of my investigation was ambiguous. I cannot certainly say that he did kill these tigers or whether he didn’t kill these tigers.

07:30

But while writing the article and meeting several people who knew him and meeting younger people who were motivated to become conservationists because of Kenneth Anderson’s work, this question became irrelevant. That was the most interesting development through the course of working on this article.

07:56

He has inspired several, I don’t know, maybe thousands of people to be aware of the importance of wildlife. Even someone like Ullas Karanth who is one of the pioneering tiger conservationists in India, also writes very sort of evocatively about his early forays into the forest with Kenneth Anderson. If you look at his book, A View from the Machan, Karanth has written about these encounters and certainly these early encounters inspired him. This is just one person, but apart from that, there must be hundreds, if not thousands more who have taken an interest in wildlife and conservation because of their reading of the Shikar literature of Kenneth Anderson.

8:52

Lalitha Krishnan: So interesting. I didn’t know any of that. Great. So, more recently you wrote a very disturbing article about how snake bites kill more Indians than all other wildlife combined. That was a real shocker. I quote your article now, “The World Health Organization has classified snake bites as a neglected tropical disease.” It’s a complicated subject to write about. So tell us about that.

9:23

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: It’s certainly complicated Lalitha, I agree with your assessment and it’s complicated for a few reasons, primarily because it’s so overwhelming, right? When you actually start looking at the statistical data, which is clearly under reported, it is scary, shocking, humongous and extremely complex.

09:54

So just to start off with some numbers. The numbers come from something called the Million Death Study (MDS), which looked at unnatural mortality among Indians. What emerged from this vast work is that more than 50,000 people were dying of snakebites in India annually, which is more than all other instances of man and animal conflict combined in the country. So it just seems it’s also complicated because it is so pervasive, right? It’s not restricted to a particular geographical region. It’s not restricted to one species of snake. And it primarily affects a certain poorer class of the country, primarily agriculturists who are out working in the field. So it just doesn’t get the media attention necessary also. For instance, if a marauding tiger accidentally encounters a human and kills that person, there’s so much attention paid to that one incident. Whereas the snakebites, over the past few months, I have sort of started following reportage of snakebite deaths. And often these are not reported. And when they are reported, they are consigned to some corner in the regional media.

11:44

And they rarely make it to the English newspapers, forget sort of the television channels because they are so widespread and common and also there is a feeling that simply because of the nature of the conflict right? A snake slithers through a paddy field; a farmer bends down either harvesting or so planting crops the snake bites the victim somewhere below the knee, on the ankle, on the talus, on the heel and slithers away. So what can you do about this? So it’s incredibly complex and it’s a bureaucratic tangle also because unlike instances of conflict with other animals where it’s usually the forest department of the respective state that becomes the mediating state authority when it comes to snake bites–even though the vast number of poisonous snakes are considered… come under the ambit of wildlife protection act these are often…I mean it’s a more wider problem. So the department of agriculture is involved, the revenue department is involved, the health department is involved, the education department is involved. So there is, I mean, it’s a bureaucratic minefield to negotiate with. So, but through the course of working on this article, I did meet some very passionate, diligent, hardworking herpetologists who are coming up with simple solutions.

13:35

For instance, in the rural hinterland of Mysuru, Gerry Martin/Gerard Martin, the well-known herpetologist has been involved in a lot of local outreach, where he, through the aegis organization is distributing gumboots to farmers and advising them not to go out late at night. I mean it’s funny, a lot of these bites happen because of erratic power supply to agricultural fields. Farmers have to pump water and electricity is provided only at night. So late at night, in the middle of the night in fact, the farmers have to go to their fields and turn on their pumps. So a lot of bites take place at this time.

So Gerry Martin by simply encouraging them to wear closed footwear, by wearing gum boots when they go out at night… when they can’t see what’s slithering around them… I don’t know the efficacy of this yet, because it’s still something that he’s put in place recently.

14:49

But there are simple solutions, but it is extremely complicated. And there are other problems as well. The state of antivenom, for instance, is a huge concern. And then also the tendency of villagers to go to a local quack, a local healer who has attained some kind of notoriety for treating victims of snakebites because of which they delay going to a hospital. All of this, you know, means that it is extremely complicated to sort of, find easy solutions to this conflict. Any issue of man-animal conflict, as I’ve reported over the past few years, is extremely, extremely complex to resolve. But when it comes to man-snake conflict, it is the problems are of another degree.

15:50

Lalitha Krishnan: Yes, it’s so complex I don’t even know what to say. As far as your conservation pieces go, you also have a knack for researching and writing about lesser-known people and topics. You wrote about a famous taxidermist also known as Van Ingen of Mysore, I don’t know if I’m pronouncing his name right either, who stuffed shikar trophies for international nobility and maharajas of India. He was considered quite an artist in “making a lion look more terrifying than it looked”. So please share some interesting facts you came upon while writing this story.

16:29

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Thank you Lalitha. This was an article that I enjoyed writing tremendously, you know, because I’m primarily interested in history so it gave me a chance to indulge in my passion for research and combine it with journalism. So this this article that you mentioned, I must congratulate you for finding this and reading this because it is written more than 10 years ago. It still remains relevant. Anyone can google for it, read it. It reads very well even now. What sparked my curiosity, if you can indulge me for a bit, is that I read a very, very sort of brief report in the newspaper, like a one paragraph report around 10 years ago if I remember correctly. And, all it said was, (Edwin) Joubert Van Ingen, leading taxidermist of Mysore passes away. That’s all, right? And the one paragraph news item stated that Van Ingen was the last member of the famous family of the Van Ingen taxidermist. And he had passed away at the ripe old age of 101. So for all these reasons I was very very intrigued.

18:01

And at just at that time I think I had read R.K Narayan’s book where the main character is a taxidermist. It’s called The Maneater of Malgudi. So for all these reasons I was very sort of intrigued and I went off to Mysore and I was so fascinated to learn more about this character. So he was the last surviving member of the Van Ingen family. So they were actually Dutch Boers who had moved to South India and Mysore at some point during the reign of the Wadiars of Mysore when Mysore was a princely state. So, Joubert Van Ingen’s father started this taxidermy firm sometime in the 1920s and he had four sons, all of whom carried on the legacy after their father’s death. and they had a vast factory.

19:10

So this was the time that you should be aware that hunting was wide bred, was considered a sort of, there are many sort of studies on hunting during the British colonial period. But hunting was in a way considered a rite of passage for both colonial officers and the Indian nobility. So, it was perhaps a valued hobby, a pastime, a networking arena if I could sort of use that very modern phrase. And everyone was hunting and they wanted to preserve this memento that they acquired for posterity.

20:01

So taxidermist became very important and it became a very skilled profession. During my research I met a number of people including employees who worked for the Van Ingen factory and other old residents of Mysore who were aware of the Van Ingens, who had spent time with them, who sort of spoke about Joubert Van Ingen’s great knowledge of the forest and his skill as a taxidermist. it is a little overwhelming for me when I recount this because as I mentioned earlier.

20:46

I mean they had a vast factory and they were the favoured taxidermist across South Asia and thousands of animals, skins primarily, would be sent to them from all over the country, right from Nepal from sort of the furthest boundaries of British India and then these thousands of skins would be processed for example if they are processing tigers they would make full mounts meaning the entire body of the tiger or like only the head or even rug right? And, we now have a population of between 3000 and 4000 tigers in India.

21:33

You will be fascinated to learn Lalitha that just sort of say in a five year period, according to the data that I discovered in the 1930s, when the factory was working at its full efficiency perhaps, more than 3000 tigers were just processed through the Van Ingen factory in five years.

21:59

This was sort of like a line. So they had sort of prefabricated models, mannequins which they would use. It was an elaborate art also. But, the Van Ingens could err and refine their models simply because they had thousands and cumulatively perhaps lakhs of animal skins being processed in their factory. So, I mean, when we look back and just say a hundred years ago, this is not even a hundred years ago, say 70-80 years ago, large carnivores were so widespread. Even then, their numbers were depleting because there was no awareness of the importance of conservation. But it was just so easy to foray into the forest, to head to the forest, kill a tiger, shoot a tiger and then transfer the skin, transport the skin.

23:11

And Van Ingens had produced several manuals which were available, I am presuming, all over the country at that time, which described in detail what a hunter was supposed to do as soon as he shot an animal, how the skin should be preserved and how it should be transported safely so that it arrives in immaculate condition and then can be transformed into this great work of art that reflects a living animal itself. So, tigers were just one animal, there were leopards, there were elephants—not full elephants–elephant heads.

23:55

Even now, if you go to the Mysore Palace, right at the entrance there are two elephant heads which are mounted at the entrance. These also have been processed by Van Ingen. In the Mysore Palace there is a restricted enclosure. Enclosure may not be the right word. A room– a state room, a huge large room where you need special permission to go. And because the Mysore Maharajas were patrons of the Van Ingens, several of their trophies are available in this room, including a mount of the pet of one of the Mysore Maharajas, a mastiff known as Brumell. So Van Ingen, Joubert Van Ingen, you know, it is unfortunate that I was a journalist even before his passing, but I was unaware of the stature of this person. And I became aware of him only after his death. And all this, I found out after his death, you know, the only great regret I have is that I never met this man when he was alive.

25:06

Lalitha Krishnan: Wow, now I understand why you were overwhelmed. I mean, a factory processing tigers and elephants. It’s hard to imagine, you know? Vikhar, both your articles, Mumbo Jumbo Responses and Tiger on the Trail, cover again a very serious matter of human animal conflict. I like that you covered both sides of the story, the people’s view and the challenges that wild animals have to face living on the edge of human habitat. Karnataka has the highest count of elephants in India according to the 2017 census and probably, correct me if I’m wrong, human deaths by elephants.

25:47

According to the National Tiger Conservation Authority’s “Status of Tiger Report” (2022), there are 3000+ tigers in the Nilgiri Biosphere. Despite ‘Early Warning Systems’, trenches, tracking, fencing, relocation, building of corridors, radio collaring etc, this again, is such a complex issue and must have been a very difficult one to cover. What were the challenges you discovered writing about these conflicts?

26;17

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Oh, thank you for that question, Lalitha. These pertain to two of my detailed articles. The first one, Mambo Jumbo Responses is on the human elephant conflict in the hills of Hassan, which has been a pervasive problem over the past few decades. And the second one is titled Tiger on the Trail, which pertains to tiger-human conflict on the fringes of two very well-known protected areas, the Nagarhole Wildlife Sanctuary and the Bandipur Tiger Sanctuary. So both of these are different. I mean, there was a point in my career, in my life when man-animal conflict issues were seen as humans encroaching into forests and because of which all this conflict takes place.

27:14 That was the sense that I had, which as I later learned, I was quite badly informed. So for instance, in the hills of Hassan, there is a resident herd, I mean it is not a single herd. There are several smaller herds and even individual male elephants who form their own bands or who are sort of rambling alone. So there are no forests, there is no protected area or even if they are there, these patches are so small and scanty that they cannot sustain this herd. So basically you have this large group of elephants that are just sort of walking around through the extensive coffee plantations in that region. So that is why you have these instances of conflict and over the past two decades. Some 70 people have been killed and various solutions have been devised but none have worked so far.

28:28

The only solution seems to be that humans and elephants need to learn to coexist and moving to the tiger issue… See, tigers in Nagarole and Bandipur… Bandipur and Nagarole are touted as sort of marquee examples of conservation success, especially of Project Tiger which began in 1970s, somewhere in the 1970s.

28:57

And when Project Tiger commenced, there were 12 tigers in Bandipur. There are more than 200 tigers and as you know, tigers are very territorial. So it is, I mean it is ironic, the conflict is a result of the success of conservation.

29:21

So these areas have been protected very well. So tigers are territorial beasts, they are also very fecund. So they have reproduced, they have taken advantage, there is a robust deer population…cheetal. So the population has grown and considering that these animals are territorial, they do end up on the fringes of these forests and even are often spotted outside the protected areas as well. So it is a little more complicated. Right? Again, through the course of writing this article where I met a variety of stakeholders there is no easy solution to issues of man-animal conflict. That’s what I realize and the intervention of non-state actors has been crucial in mitigating instances of human-animal conflict.

30:18

Lalitha Krishnan: Thank you for that. You gave a good explanation or understanding of what the real issues are. So, Vikhar, as a fellow of the Asian Journalism Fellowship, you were lucky to listen to Jane Goodall in Singapore. Your wonderful and erudite article, The Chimpanzee Lady, I presume is inspired by this encounter. So what was the most inspiring thing (I am sure there are a zillion) about her that influenced this article?

30:51

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Lalitha, it’s kind of a very sort of basic question. It’s not a question at all. Because well, Jane Goodall… but we need to go back to the time that we spent together at Wildlife Institute of India (WII ) and one of the classes there which was a discussion on wildlife literature.

31:22

So I carefully sort of made a list of all the books that were recommended and the first book that I read once I came back from Dehradun back to Bangalore was Jane Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man. And I felt so deeply moved by that book and the honesty of Jane Goodall and her sincere effort at conducting what is now clearly seen as pioneering research on the ethology, on the behavior of chimpanzees that I sort of told myself that if ever an opportunity presented where I could listen to this great lady directly,I’ll sort of move heaven and earth to get there. Coincidentally, after that time after reading her book I was in Singapore and she was speaking at a venue in Singapore. And in Singapore, unlike a lot of events in India where everything is free and people can just walk in where in fact there’s a paucity of attendees sometimes… Singapore, it was a ticketed event. Someone, I think if I recall correctly, my fellowship administrators procured a ticket for me after they became aware of my eagerness to listen to Jane Goodall. So I went. I listened to her. Jane Goodall’s work is fascinating on many many levels. There are many other greater people who can comment more authoritatively on the extensive corpus of her work. But for me, what struck me was, I haven’t gone through advanced postgraduate academic studies. It’s very difficult to challenge the established discourse that has been set in academia. It can be in any discipline.

33:41

So Jane Goodall goes to Gombe in Tanzania and she doesn’t have any background, she doesn’t have a degree even in wildlife sciences or anthropology or anything and very intuitively starts studying the chimpanzees of Gombe and builds such profound relationships with generations of chimpanzees. And she writes very beautifully about this connection that she built. So I heard her and also a very interesting point that she made was at some point, Goodall does enrol for a PhD and even completes it at Cambridge University. But when she realises that her research has greater significance, she very brutally, very confidently disconnects with academia, which I think is a very bold sort of move to make because how do we legitimize knowledge, right?

34:57

How do we legitimize that a certain mould of research is the correct way? We strive for recognition by a peer community and she breaks away from this and moves full-time into conservation. She says, no, I don’t want to be a wildlife scientist.

35:20

She takes this decision sometime in the 1980s. She’s done so much for conservation all over the world. What I recall very sort of clearly, is how optimistic she is. You and me are perhaps more pessimistic but even at her advanced age she remains very optimistic that humans and animals in the wild can coexist.

35:51

Lalitha Krishnan: What conservation needs! Hope. Optimism. I think she’s 90 now and still inspiring so many generations. She’s amazing. I had to ask you that question. I’m sorry. Besides, I am so jealous… Thanks for that, Vikhar. And, this is for budding conservationists or journalists, writers and documenters. What guidelines would you suggest for ethical representation?

36:22

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: That’s a tough question, Lalitha.

Lalitha Krishnan: Well, they can just read your articles.

36:29

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Yes, yes, I certainly recommend that. Along with that, see, I mean, I came to writing about issues of wildlife and conservation in a convoluted way. At a midpoint in my career, I’d like to think… I’ve been a journalist for 16 years now. So I started paying attention to issues of man-animal conflict /conservation only over the past few years. So before that, my journalistic sense was finally honed. So using that same methodology and tools, I sort of applied it to understanding issues of conservation.

37:21

And very practically, what I did is, first, I befriended wildlife scientists as well as conservationists. And there is a fine difference between these two categories of people. I befriended these people who are working towards on issues of conservation and then started sort of hanging out with them and getting a sense of how they engaged and interpreted issues of wildlife because wildlife science is a very advanced discipline. So obviously I couldn’t master it, right? But I tried to familiarize myself with how they think, how they thought. And using this sort of connection, I gained the confidence of writing on these issues. So these friends have been of great help.

38:32

When it comes to issues of conflict, again, I sort of work very clearly in a very straightforward manner as a journalist. Some people who identify themselves only as environmental writers or wildlife writers make the mistake of approaching the story with a bias. The bias is towards animals and even me, I mean, the whole purpose of my work is to ensure that how conservation can be improved. But I sort of don’t go to the field with this bias. I go with a very open mind and issues of conflict are extremely complex, right? They cannot be seen in terms of a black and white understanding.

39:19

They are very grey, they are very complicated and I enjoy that process of unravelling the intricate complexities of these issues. So, I savour that challenge. So, my advice to people who are writing about the wildlife and issues of conflict especially, is to be aware that there are multiple stakeholders and it’s very tricky to sort of unravel the complexities of conflict. But the advantage with these stories is first that wildlife. Scientists and conservationists are very studious people, right? So you have an incredible and rich source from which you can draw.

40:07

These people have been thinking so they would have generated data, they would have a strong perspective, they would have developed a strong point of view. So that is one advantage compared to the reportage that I do on other issues. I report in Karnataka and the bureaucrats of the forest department—I don’t know, I can’t speak for the forest department bureaucrats in other states—but at least in Karnataka are accessible, which means that to understand the state point of view, the government point of view, you have an avenue for a journalist or for a writer. Because, like I’ve mentioned that I report on a wide variety of issues, right? Agriculture, caste issues… communalism. Often my struggle is to gain access to an officer or a bureaucrat of some authority who can comment articulately and clearly on an issue, which half the time is a big struggle.

41:19

Whereas when it comes to issues of wildlife, there is some struggle. People are not sitting as soon as you call them, they are just waiting, rolling out the red carpet for you. But at least they are willing to talk, which is important. So those are some learnings. And I don’t know if it works as advice, but certainly those are learning and which is why I’m excited to write more about issues of wildlife and conflict from Karnataka.

41:48

Lalitha Krishnan: I so look forward to that. Thank you so much.

41:51

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed: Thank you. You’re welcome Lalitha. I mean, I’m so happy that we had this conversation because I know that, you keenly read my articles. So it’s always a pleasure engaging with someone who takes your work seriously, who pays close attention to it. I should thank you for taking the time to read, go through some of my own articles, which I had forgotten.

42:20

Lalitha Krishnan: Absolutely my pleasure. I learnt so much. From listening to you even more.

The end.

Listen to the podcast here.